Archival Context

This article reconstructs the seminal insights presented by Dr. Janet Woodcock, Director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) at the FDA, during the 2016 Cardiac Safety Research Consortium (CSRC) proceedings. The presentation, titled “Drug and Device Development: Balancing Benefit and Risk,” outlined the FDA’s strategic shift towards a structured, qualitative framework for decision-making, with a specific emphasis on incorporating patient experience data into the regulatory review process.

Executive Summary

The approval of a new medical product involves a complex calculus. It is rarely a binary choice between “safe” and “unsafe.” Rather, it is a probabilistic assessment of whether the potential benefits to a specific patient population outweigh the potential risks. In 2016, Dr. Janet Woodcock articulated a transformative vision for the FDA: moving from an implicit, internal judgment process to a transparent, structured Benefit-Risk Framework.

This framework is particularly critical for rare diseases and conditions with high unmet medical needs, where patients may be willing to accept higher uncertainty or safety risks. As referenced in Advances in Therapy, integrating patient and caregiver perceptions into this calculus is no longer optional—it is a regulatory mandate.

However, the “Risk” side of the equation begins long before a clinical trial enrolls its first patient. Dr. Woodcock’s framework implies that rigorous pre-clinical safety profiling—utilizing high-purity chemical probes and toxicity screening libraries—is the foundational layer upon which all subsequent risk-benefit decisions are built.

The Structured Benefit-Risk Framework

Dr. Woodcock emphasized that the “Benefit-Risk” assessment is not a mathematical formula but a qualitative judgment informed by quantitative data. To standardize this, the FDA implemented a five-part grid that guides reviewers through the decision-making process.

Table 1. The FDA’s Structured Benefit-Risk Framework Grid

| Framework Component | Evidence and Uncertainties | Conclusions and Reasons |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis of Condition | Severity of disease and impact on patients. | Establishes context for risk tolerance. |

| Current Treatment Options | How well patients are served by existing therapies. | Identifies unmet medical needs. |

| Benefit | Does the drug work? (Derived from RCTs). | Endpoints: Survival, functional improvement. |

| Risk | Frequency, severity, and reversibility of side effects. | Covers on-target and off-target toxicities. |

| Risk Management | Can the risks be mitigated? (REMS, Labeling). | Final decision on marketability. |

Patient Experience Data – The New Frontier

One of the most significant pivots discussed by Dr. Woodcock was the formal inclusion of Patient Experience Data (PED). Historically, “Benefit” was defined by clinicians. The 21st Century Cures Act and PDUFA V initiatives pushed for the patient’s voice to define what constitutes a meaningful benefit.

In rare disease trials, a statistical improvement in a biomarker might not translate to a feeling of wellness. Conversely, a small functional gain might be invaluable to a patient. When developing drugs for niche indications, researchers often start with target validation using small molecule inhibitors in phenotypic assays. Understanding the patient’s phenotype helps guide which molecular targets (and thus, which chemical tools) are prioritized in the discovery phase.

The Foundation of Risk Assessment – Pre-Clinical Toxicology

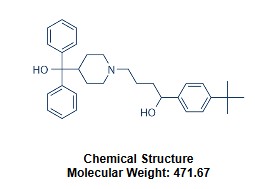

While Dr. Woodcock’s presentation focused on clinical regulation, she acknowledged that the “Risk” profile is largely inherited from the molecule’s chemical properties. Before a Benefit-Risk assessment can occur in humans, a “Safety Margin” must be established in the lab.

This involves Target Selectivity Profiling: Ensuring the drug candidate hits the intended target without inhibiting critical safety targets, such as Calcium Channel Transmembrane Transporters.

Translating Safety Signals to Clinical Monitoring

To reduce uncertainty, the FDA advocates for the use of Safety Biomarkers. The validation of these biomarkers depends on high-quality chemical biology tools. Researchers use specific inhibitors to induce toxicity in controlled cellular models, verifying that the biomarker rises in response to the specific insult.

Benefit-Risk in the Era of Precision Medicine

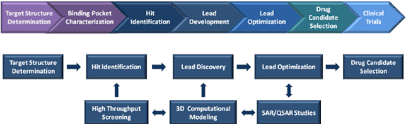

The future of the Benefit-Risk framework lies in Precision Medicine. A “dirty” drug with broad kinase inhibition might have an unacceptable profile. However, a selective inhibitor designed to target only the mutant protein might offer a pristine safety profile. This necessitates the use of High-Throughput Screening (HTS) libraries during discovery to find that “magic bullet” with the perfect selectivity score.

References

- Woodcock, J. “Drug and Device Development: Balancing Benefit and Risk.” CSRC Meeting, 2016.

- FDA. “Benefit-Risk Assessment in Drug Regulatory Decision-Making.” 2023.

- The Case for the Use of Patient and Caregiver Perception of Change Assessments. Advances in Therapy, 2019.

- PDUFA V: Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative. U.S. FDA.