Abstract

Rivaroxaban is a direct-acting oral anticoagulant approved to prevent strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation. Dosage recommendations are approved for all adult patients to receive either 15 mg or 20 mg once daily depending upon renal function. There are a number of reasons to believe rivaroxaban dosing could be more effective and/or safer for more patients if increased dosing precision is available.

Because real-world patients are more diverse than those studied in phase III clinical trials, we evaluated the extremes of creatinine clearance (CrCl) on rivaroxaban clearance using a published population pharmacokinetic model and applying exposure variation limits (±20%) based on published literature. The proposed dosing recommendations are: 10 mg once daily (CrCl 15–29 ml/min), 15 mg once daily (CrCl 30–69 ml/min), 10 mg twice daily (CrCl 70–159 ml/min), 15 mg twice daily (CrCl 160–250 ml/min). These new dosing recommendations should be prospectively tested for predictive accuracy and to assess the impact on AF patient efficacy and safety.

Study Highlights

What is the current knowledge on the topic?

Rivaroxaban is a relatively safe and effective treatment for atrial fibrillation in preventing strokes, but may be relatively inferior to the other direct-acting oral anticoagulants for efficacy or safety. There is evidence that rivaroxaban efficacy and safety could be increased with more precise dosing.

What question did this study address?

More precise rivaroxaban dosing recommendations are provided for a wider patient range of creatinine clearance than was studied in the phase III trial, but which exist in real-world patients.

What does this study add to our knowledge?

Dosage recommendations have been provided for a broader range of patient renal function than was previously available.

How might this change clinical pharmacology or translational science?

The methods used in this study could be applied to other drugs where the label provides dosing that may not be suitable for all patients who will use the drug.

Introduction

Drug dosing recommendations in the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved label are influenced by the science-based strategy behind the key phase III clinical trials as well as the marketing strategy to support postapproval sales goals. FDA guidances regarding special patient characteristics that may influence dosing in the real-world population also shape drug dosing. The real-world patient population is often much more diverse than in the sample studied in the phase III trials, which can result in efficacy, safety, and dosing gaps between these trials and real-world patients. This is a particularly concerning problem for drugs in which either under- or overdosing could result in death or severe morbidity.

We believe that the relatively new direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs; dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban) used to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) represent an opportunity to improve efficacy (by reducing stroke incidence) and safety (by reducing incidence and severity of major bleeding episodes) by more precise dosing than is currently available. We have chosen rivaroxaban to begin developing precision dosing for AF, as it has been one of the most frequently prescribed DOACs in the United States. There is evidence rivaroxaban may be less effective or safe than the other DOACs with the approved dosing strategies. We believe more precise dosing could improve rivaroxaban’s efficacy and safety.

We are only focusing on AF, although rivaroxaban is also approved for the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism and acute coronary syndrome. AF was chosen because it is the most commonly prescribed rivaroxaban indication and patients may continue taking it for life. Rivaroxaban inhibits Factor Xa inhibitor in a concentration-dependent manner so that the degree of anticoagulation (i.e., prothrombin time (PT)) directly mirrors rivaroxaban plasma concentrations as they rise and fall after oral administration.

The dosage regimen approved by both the FDA and the European Medicines Agency is: 20 mg once daily in patients with creatinine clearance (CrCl) >50 ml/min; 15 mg once daily in patients with CrCl between 15 and 50 ml/min.

Like all DOACs, rivaroxaban has the advantage of dosage simplicity over warfarin because there is no need for international normalized ratio laboratory testing and feedback-based dosing. One potential dosing advantage rivaroxaban has over other DOACs is that it is only dosed once daily for AF.

We have evaluated the degree to which dosing as specified in the rivaroxaban label would result in drug exposure likely to be consistent with drug plasma concentrations close to the levels for the average patient in the pivotal efficacy‒safety trial. Although real-world patients who need anticoagulation do have both renal function and size extremes well beyond that experienced in phase III trials or accounted for in the label, our recommendation is to use a CrCl-based method over a weight-based method because renal function is expected to contribute more to overall rivaroxaban exposure than body weight. This premise is supported by publications suggesting the effect of body weight on drug exposure is minimal and certainly less than the effects seen with CrCl. Although there is evidence that either PT or drug concentration feedback-based dosing may have additional advantages, we have not addressed this potential.

Methods

The fundamental assumption used in estimating more precise dosing for a wider range of renal function than was experienced in the phase III clinical trial is to match drug exposure (i.e., average rivaroxaban 24-hour steady-state area under the plasma concentration-vs.-time curve (AUC)) from the average patient in the clinical trial to patients with varying CrCl without exceeding a 20% change in AUC for reasons specified in what follows. It is assumed that exposure matching will result in similar benefit and risk regardless of dosing frequency.

The underlying model that was used for all pharmacokinetic (PK) calculations, including scaling of AUC and maximum drug concentration was described by Willmann et al. along with a supplementary file containing the final model code. This model is based on 4,918 clinical study patients with PK data from phase II and III clinical studies for multiple indications. The model holds that apparent rivaroxaban clearance is significantly affected by actual body weight, CrCl, study/indication, and comedications. Apparent volume of distribution is affected by actual body weight, age, and sex. Bioavailability in the model decreases as dose increases, which is congruent with dedicated PK studies of rivaroxaban.

The model structure, parameters, and covariate relationships presented in the model were utilized to describe the expected PK of rivaroxaban. Parameter values were fixed to the published final estimates. The value of the “STUDY” covariate that impacted predicted clearance was fixed at 0.849, which was the final estimate for the AF indication. The value of the “COMED” covariate was fixed at 1.0, which reflected the scenario where no comedications were present. Although comedication effects on clearance were omitted, it is worth noting that the magnitude of comedication effects on rivaroxaban exposure in the study by Willmann et al. was much smaller than that observed in clinical drug‒drug interaction studies, possibly due to the small proportion of patients receiving relevant comedications in the Willmann et al. dataset.

The covariates of CrCl, weight, and age were centered around the average values from the Willmann et al. dataset (93 ml/min, 81 kg, and 61 years old, respectively), because Willmann et al.’s final parameter estimates for covariate effects were utilized. To focus on average predictions, all between-subject variability, within-subject variability, and residual variability data were removed from the original model. This meant that our strategy was more akin to a calculation rather than a true population PK simulation. The final equations for apparent clearance (Eq. 1), apparent volume of distribution (Eq. 2), and relative bioavailability (Eq. 3) were recoded from the supplemental NONMEM code file from Willmann et al. as functions into R software. Supplementary File 1 contains the code for these functions in R along with comments to facilitate use of these functions according to our methods.

where CL denotes drug clearance, CrCL denotes creatinine clearance, WT denotes body weight, AGE denotes biologic age (in years), F denotes relative oral bioavailability, Fmin and Fmax are estimated parameters, TV subscript denotes the typical (population) value, DOSE denotes the administered dose of rivaroxaban (in milligrams), STUDY denotes effect of the type of study, COMED denotes effect of drug-drug interactions between rivaroxaban and certain comedications.

The ROCKET-AF data utilized in the Willmann model had a mean (SD) of 81.76 (32.06) ml/min for CrCl. Although the range was not reported for CrCl, it was likely considerably narrower than those reflective of real-world patients and the values used in our simulations. The underlying structural covariate models were based on data that were narrower in range compared with real-world patients, yet were assumed to extend to the wider real-world patient ranges, and thus we suggest the proposed doses and regimens be prospectively tested.

To determine the values of CrCl and body weight to use to define a target reference patient for scaling purposes, we utilized the average measurements from the ROCKET-AF patient sample to create a virtual patient who was 73 years old, weighed 73 kg, and had a CrCl of 68 ml/min. This virtual patient was administered 20 mg once daily. Rivaroxaban currently does not have a defined therapeutic window, but clinical response depends on exposure. Other DOACs, such as dabigatran, have more clearly characterized exposure/response relationships, which suggest there may be an optimal plasma drug concentration range. The mechanisms behind the exposure/response relationship are likely similar in all DOACs, and higher exposures of rivaroxaban were assumed to increase the risk of bleeding, whereas lower exposures increased the risk of stroke. It was also assumed that patients taking rivaroxaban can achieve a balance where efficacy is maximized and adverse events are minimized.

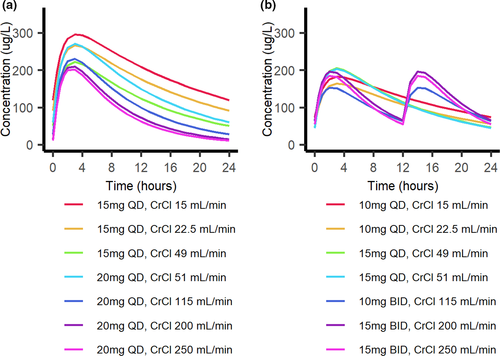

To determine the optimal dose and regimen, the PK profiles and AUCs of several once-or-twice-daily dosing regimens (with a total daily dose ranging from 5 to 60 mg/d) were calculated in virtual patients. Currently-approved rivaroxaban doses for AF are given once daily, but twice-daily dosing regimens were also considered. This was due to the dose-dependent bioavailability of rivaroxaban, which can result in different 24-hour exposures for the same total daily dose if it is given once or twice per day, as well as the potential risk of increased adverse events with extremely high peak concentrations and decreased efficacy with extremely low trough concentrations.

Every CrCl value between 15 and 250 ml/min was evaluated for a 73-kg virtual patient for each dosing regimen. This range of CrCl was determined to be physiologically relevant for adults, and rivaroxaban is not recommended in patients with a CrCl <15 ml/min. All virtual patients were male and 73 years old. The predicted PK profiles and AUCs were evaluated to identify dosing regimens, which yielded predicted AUCs within ±20% of the target AUC at each value of CrCl. It was assumed that the outcome would be optimal as long as the AUC is within 20% of the target AUC.

Results

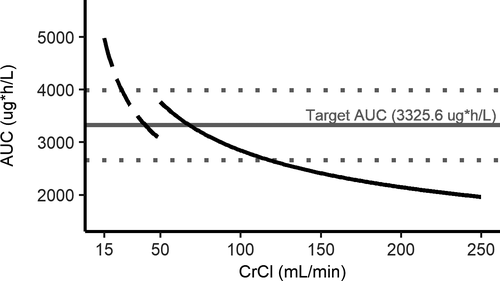

The average 24-hour steady-state AUC is 3,325.6 μg/h per liter for a 20-mg once-daily dose administered to the average 73-year-old male patient weighing 73 kg with a CrCl of 68 ml/min, as calculated using equations from the Willmann et al. model and patient characteristics from the phase III atrial fibrillation trial. The calculated average peak and trough concentrations for this virtual average patient are 255.2 μg/L and 46.6 μg/L, respectively. The ±20% AUC lower and upper bounds are 2,660.5 and 3,990.7 μg/h per liter. The calculated Rivaroxaban reference AUC of 3,325.6 μg/h per liter served as the target AUC.

To determine the impact of renal function on rivaroxaban steady-state exposure, the predicted AUC was calculated for the average AF patient with a CrCl that increased in 1-ml/min increments from 15 to 250 ml/min. The predicted AUCs were then compared with the reference AUC for the average patient with a CrCl of 68 ml/min to match the median CrCl in atrial fibrillation patients, as shown in Figure 1.

With the currently approved rivaroxaban dosing, the threshold CrCl values that crossed the upper and lower 20% reference bounds were 26 and 117 ml/min, respectively. Acceptable dose amounts based on renal function were selected for patients above and below the 20% reference values by matching AUC and then creating a change in dosing interval if needed to approximate the reference rivaroxaban peak and trough. Acceptable dosing regimens were then grouped into a strategy based on renal function (Table 1), which kept the predicted AUC close to the target AUC along the entire tested CrCl range. The model-predicted 24-hour steady-state rivaroxaban AUCs according to this novel strategy is presented in Figure 2.

Table 1. Creatinine clearance (CrCl)-based strategy for rivaroxaban dosing in adults with atrial fibrillation

| CrCl (ml/min) | Dose |

|---|---|

| <15 | Not recommended |

| 15–29 | 10 mg once daily |

| 30–69 | 15 mg once daily |

| 70–159 | 10 mg twice daily (20 mg/d) |

| 160‒250 | 15 mg twice daily (30 mg/d) |

a CrCl calculated using Tietz-truncated Cockcroft‒Gault equation with actual body weight.

Discussion

It is informative to review the evidence comparing adjusted-dose warfarin to placebo for stroke along with the various warfarin‒DOAC noninferiority results. Feedback-based dosing of warfarin for AF patients produces a 64% reduction in stroke and a 26% decrease in all-cause mortality compared with placebo according to a published meta-analysis. A separate meta-analysis showed that fixed doses of DOACs compared with warfarin feedback-based dosing in AF produced a 19% reduction in total strokes or systemic embolic events, a 51% decrease in hemorrhagic stroke, a 10% decrease in all-cause mortality, and a 52% decrease in intracranial hemorrhage. However, it also showed a 25% increase in gastrointestinal bleeding compared with warfarin.

Could it be that the observed differences in outcomes between DOACs are related to how well the currently marketed individual DOAC dosing schemes (dosage, interval) perform rather than differences in the chemical moieties? By using more precise rivaroxaban fixed dosing, could rivaroxaban overall efficacy come closer to dabigatran and safety closer to apixaban? Could a feedback-based rivaroxaban dosing scheme outperform the other DOACs with fixed dosing and warfarin-adjusted dosing for efficacy and safety?

Historically, both oral and parenteral anticoagulants have been dose-adjusted based on the individual pharmacodynamic end point of the patient. The introduction of DOACs about 10 years ago has been notable in that these drugs apply relatively fixed dosing with no need for individual patient dose adjustment. This is remarkable in that DOAC changes in drug plasma concentration produce an instantaneous change in PT or partial thromboplastin time.

Selecting a preferred oral anticoagulant in AF patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CrCl <30 ml/min) is difficult for several reasons. Patients with CrCl <25 ml/min were excluded from the phase III DOAC clinical trials. We have shown the rivaroxaban dose for patients with a CrCl between 15 and 29 ml/min should be decreased from 15 mg/d to 10 mg/d. Although warfarin is often recommended in these patients, there is a four- to fivefold higher bleeding risk when using warfarin in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease compared with patients with normal renal function.

The recent FDA precision dosing public meeting highlighted the potential importance of developing more precise dosing for drug-disease targets where the potential outcome from under- or overdosing could result in serious morbidity or even death. One senior FDA physician indicated this could be the third major milestone (the age of dosing individualization) in drug development and regulation after the ages of safety in 1938 and efficacy in 1962.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Ned McWilliams, JD, of Levin Papantonio, PA, for his early contributions and unrestricted financial support, and Farah Al Qaraghuli, MS, for an invaluable review of the equations and code that were utilized.

Funding

This study was supported by the Eshelman Institute for Innovation at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy. R.K. receives a stipend for a pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics postdoctoral fellowship from the UNC/IQVIA.

Conflict of Interest

J.H.P declares consulting and research support from Novartis and research support from Amgen, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim. D.G. received a travel grant through University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to give a presentation at Boehringer Ingelheim. A.K.G. has received grant funding from Bristol Myers Squibb; consulting income from Biosense-Webster; and speaker honoraria from Zoll Medical, Boston Scientific, and Abbott. All other authors declared no competing interests for this work.

Author Contributions

J.R.P., R.K., D.W., D.G., Y.C.C., P.W., A.K., and A.G. wrote the manuscript; D.W., J.R.P., and R.K. designed and performed the research; and R.K. and D.W. analyzed the data.

References

- Spong, C.Y. & Bianchi, D.W. JAMA 319, 337–338 (2018).

- Eichler, H.-G. et al. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 10, 495–506 (2011).

- Powell, J.R. JAMA 313, 1013–1014 (2015).

- Gonzalez, D. et al. Clin. Transl. Sci. 10, 443–454 (2017).

- Gupta, K. et al. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 24, 1116–1127 (2018).

- Barnes, G.D. et al. Am. J. Med. 128, 1300–1305.e2 (2015).

- Graham, D.J. et al. JAMA Intern. Med. 176, 1662–1671 (2016).

- Ruff, C.T. et al. Lancet 383, 955–962 (2014).

- FDA CV Advisory Committee Transcript. (2011).

- Package insert for Xarelto (rivaroxaban). Janssen.

- Kubitza, D. et al. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 61, 873–880 (2005).

- Douxfils, J. et al. J. Throm. Haemost. 16, 209–219 (2018).

- Eikelboom, J.W. et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2, 566–574 (2017).

- European Medicines Agency. Xarelto EPAR Report. (2012).

- Trujillo, T. & Dobesh, P.P. Drugs 74, 1587–1603 (2014).

- ACC. DOAC dosing for AFib infographic. (2018).

- Barsam, S.J. et al. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 1, 180–187 (2017).

- Kubitza, D. et al. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 47, 218–226 (2007).

- Chan, N. et al. Am. Heart J. 199, 59–67 (2018).

- Rottenstreich, A. et al. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 45, 543–549 (2018).

- Temple, R. CSRC Presentation. (2015).

- Willmann, S. et al. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 7, 309–320 (2018).

- Mueck, W. et al. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 53, 1–16 (2014).

- US FDA OTS Review. (2011).

- Patel, M.R. et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 883–891 (2011).

- Fordyce, C.B. et al. Circulation 134, 37–47 (2016).

- Testa, S. et al. J. Thromb. Haemost. 16, 842–848 (2018).

- Eikelboom, J.W. et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 1319–1330 (2017).

- Sennesael, A.-L. et al. Thromb. J. 16 (2018).

- Kubitza, D. et al. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70, 703–712 (2010).

- Hart, R.G. et al. Ann. Intern. Med. 146, 857–867 (2007).

- Quick, A.J. Circulation 24, 1422–1428 (1961).

- Raschke, R.A. et al. Ann. Intern. Med. 119, 874–881 (1993).

- Connolly, S.J. et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 1139–1151 (2009).

- Granger, C.B. et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 981–992 (2011).

- Giugliano, R.P. et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 2093–2104 (2013).

- Ieko, M. et al. J. Intensive Care 4, (2016).

- Reilly, P.A. et al. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 321–328 (2014).

- Ruff, C.T. et al. Lancet 385, 2288–2295 (2015).

- Boehringer Ingelheim Pradaxa Strategy. (2012).

- Steinberg, B.A. et al. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 68, 2597–2604 (2016).

- Chan, K.E. et al. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 2888–2899 (2016).

- Chew-Harris, J.S.C. et al. Intern. Med. J. 44, 749–756 (2014).

- Frost, C. et al. Clin. Pharmacol. 6, 179–187 (2014).

- Roy, A. Forbes. (2012).

- Mehrotra, N. et al. Drug Metab. Dispos. 44, 924–933 (2016).

- Girgis, I.G. et al. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 54, 917–927 (2014).

- Solms, A. et al. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 8, 805–814 (2019).

- Hernandez, I. et al. JAMA Intern. Med. 175, 18–24 (2015).

- US FDA OTS Precision Dosing. (2019).

- McCaughan, M. Pink sheet. (2019).